An exploration of the game at

the heart of ‘The Master of Go’

There's something

about go that lends itself to

narrative, and perhaps no book gets inside this better than Yasunari

Kawabata's

chronicle of a pivotal 1938 match that ended exactly 78 years ago today.

BY TYLER ROTHMAR STAFF WRITER

| The Chinese board game of go has fallen

in and out of fashion over the past 2,500 years. In China during the Han Dynasty (206

B.C.-A.D. 220), go was seen as a pastime for gamblers and layabouts,

but by the

1600s it had come to rank among the “four arts” in which gentlemen were

expected to be proficient. In Japan, it became the pursuit of warriors

and the

aristocracy from as early as the 8th century. Today the game is rich in

lore,

and stories of encounters on and around the board abound. In 1835, for example, in what came to be

known as the “blood-vomiting game,” discord between rival go maestros

led one

ailing pupil to provoke his teacher’s nemesis. The match took just over

a week

and eroded the young challenger’s health to the point that, upon

losing, he

spat up blood on the board — and died two months later. There’s something about go that lends itself to narrative, and perhaps no book gets inside this better than Yasunari Kawabata’s chronicle of a pivotal 1938 match. “Meijin” (“The Master of Go”) is also the only one of his novels he considered to be finished. The battle at its center ended exactly 78 years ago today. |

|

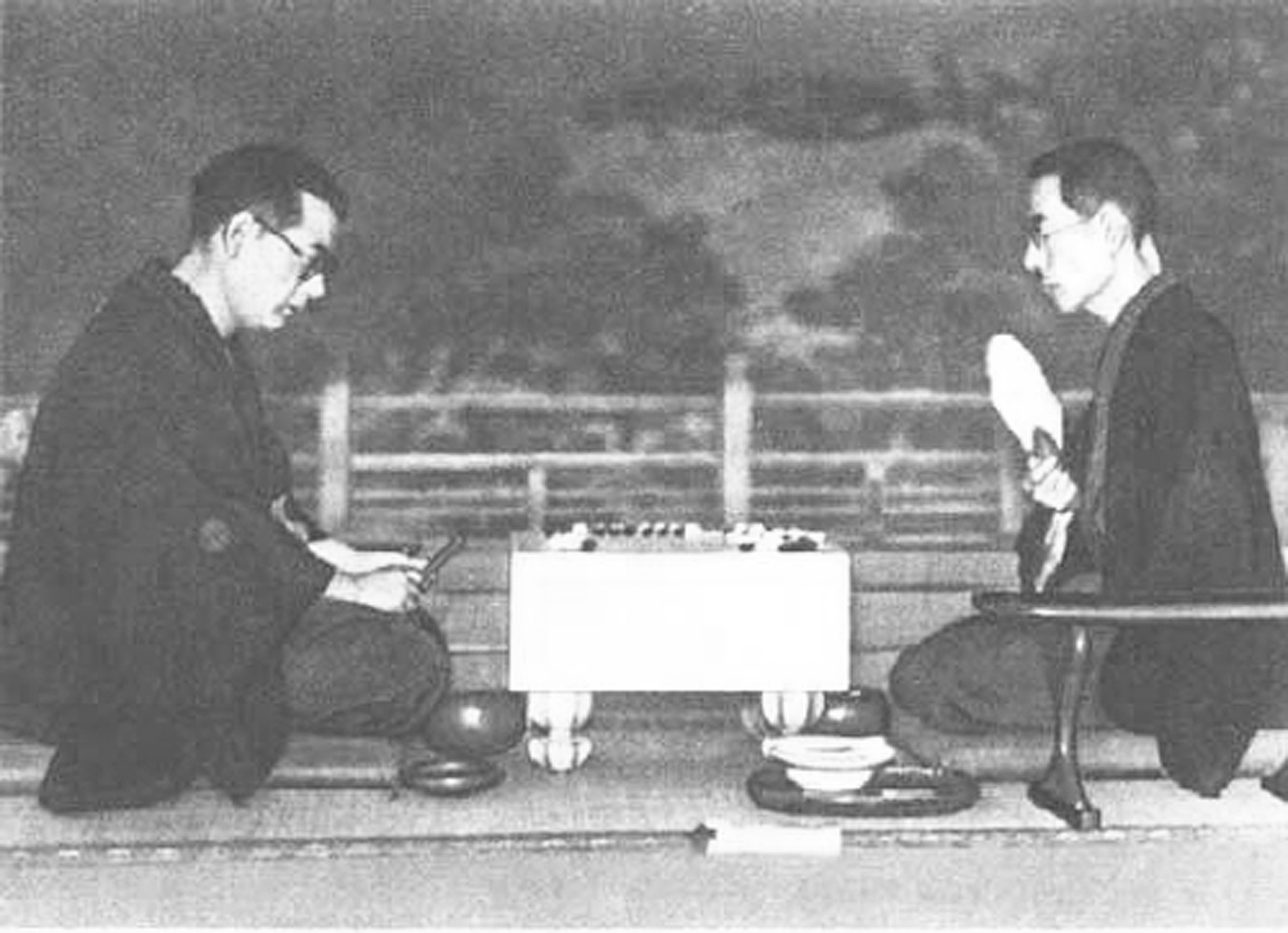

Slow war: Minoru Kitani (left) faces off

Honinbo Shusai in 1938

The last Honinbo

The monthslong contest ended on Sunday, Dec. 4, 1938, at

a ryōkan (traditional

inn)

in the coastal town of Ito, Shizuoka Prefecture. The two men, Honinbo

Shusai

playing white and Minoru Kitani playing black, agreed to see out the

last moves

of what had become a much-debated and closely followed match.

A newspaper, the Tokyo Nichinichi

Shimbun, now called the Mainichi Shimbun, had sponsored the competition

to spur

sales and sent Kawabata — then 30 years away from winning the Nobel

Prize — to

report on it. His missives were serialized in the paper, becoming

popular even

among people who didn’t know how to play. In 1954, “Meijin” was

published,

based on his reporting and experiences.

The match was extraordinary for several

reasons, not least because it took nearly six months to complete. In

the end,

the champion of the old style of play was toppled by one of the

vanguard’s

young spearheads — it was the end of an era.

Beginning in 1612, a state-sponsored

system gave rise to four dynastic go schools, of which the Honinbo were

by far

the strongest. Government patronage ended with the Edo Period

(1603-1868), but

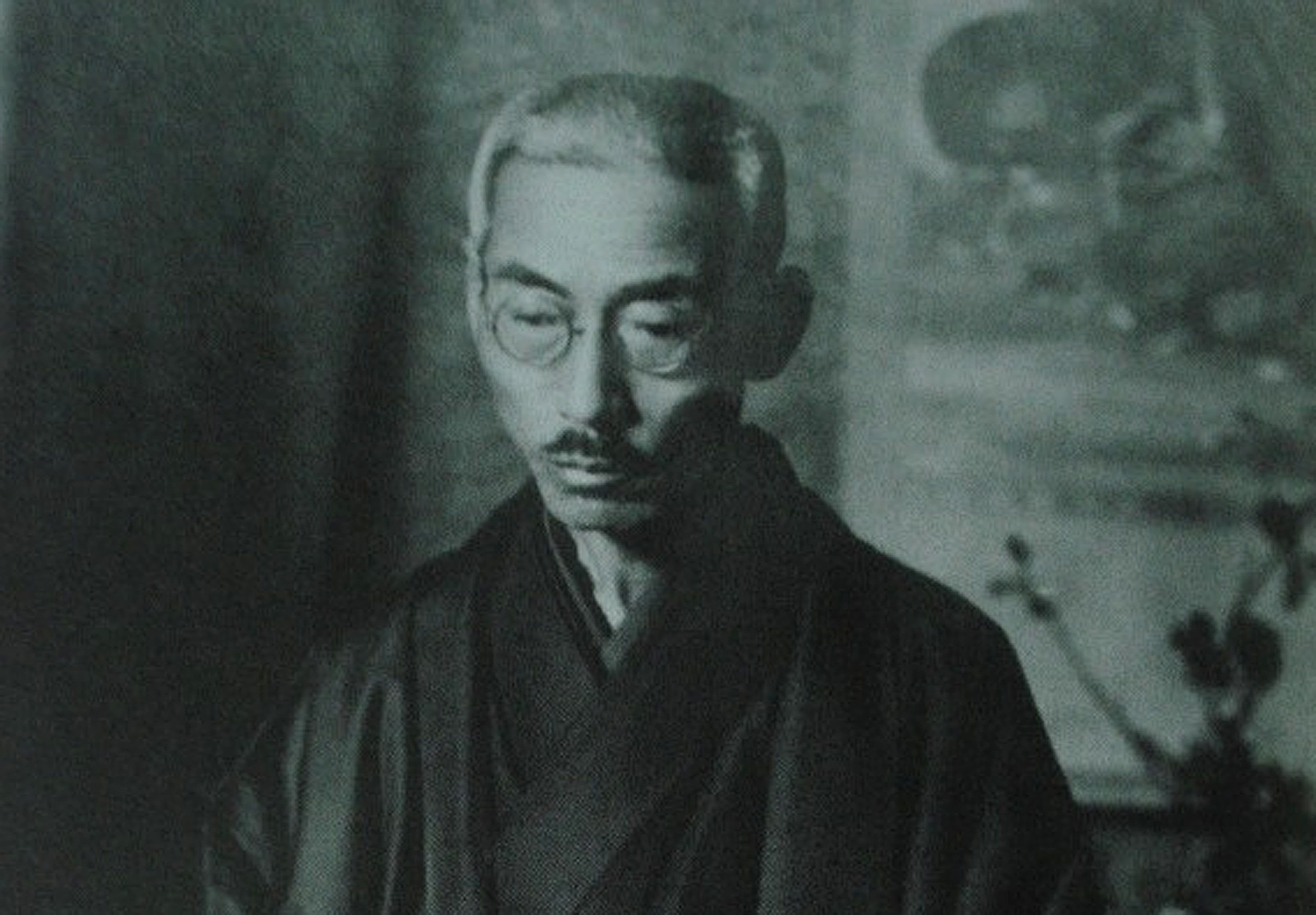

some of the old schools persisted. Shusai, the man at the center of

Kawabata’s

account, was the last of the Honinbo.

Shusai also held the title of meijin (master).

He chose to sell his Honinbo title to the Japan Go Association before

retiring

in 1936, effectively ending his line, but he was coaxed into a final

match in

1938 by the Nichinichi for a price.

As Kawabata notes, Shusai’s moniker,

“invincible,” was at odds with his frail frame and weak constitution

(he had a

heart condition). At one point, Kawabata quotes a doctor as saying that

Shusai

had “a body like an undernourished child.” But he was still meijin, and

was

regarded as the strongest living player at the time. On the other side

of the

board was Kitani, to whom Kawabata gives the fictional name “Otake.”

Among the few similarities between go

and chess is the frequent use of opening patterns, scripted dances that

precede

creative play. By the early 20th century, these had become somewhat

calcified

and dogmatic, and Kitani, along with his famous contemporary Go Seigen

(referred to in the book by his Chinese name, Wu), were leading a new

wave of

innovation in the opening game. Seigen had faced Shusai in a 1933 match

dubbed

“The Game of the Century,” but was beaten after trying a radical

opening.

The levity of Kawabata’s fictionalized version of Kitani — he cracks jokes, drinks tea relentlessly and forever excuses himself to use the facilities — belies a ruthless, ironclad will on the board. He’d won a yearlong tournament to determine who would face Shusai in the 1938 match, besting two of his teachers in the process, and was determined not to lose.

Throwing stones

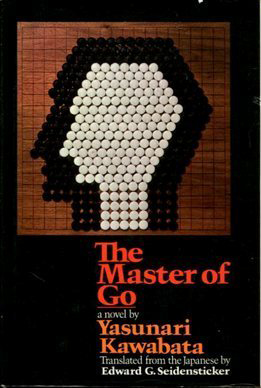

“The game of Go is simple in its

fundamentals and infinitely complex in the execution of them,” writes

Edward G.

Seidensticker in the introduction to his 1972 translation of “The

Master of

Go,” and appreciation of the book increases with understanding of the

game.

In 1996, Russian grandmaster Garry

Kasparov lost his first chess game against IBM’s Deep Blue

supercomputer. In

chess, there are only a handful of effective moves at any given time,

and Deep

Blue had the computational brawn to map out likely permutations before

choosing

the best one. Go, by contrast, is played on a much larger board with an

exponentially larger number of permutations. The possibilities are

essentially

endless, and artificial intelligences have only recently become able to

beat the

strongest humans using a rudimentary kind of intuition.

In go, all 361 points of the board start

off open. Players, taking either black or white, place stones in turn

with the

aim of surrounding more empty points than their opponent. While the

goal is to

surround territory, it is also possible to surround enemy stones, which

are

then removed from the board as prisoners.

There are deep connections between go

and military strategy, and many ways to conduct a campaign. Some

players love

to fight from the outset, while others seek to fortify and expand their

positions incrementally without being dragged into a close-quarters

scrap early

in the game.

These are the kinds of terms in which go

is discussed, and close study of the game will reveal a broad lexicon

and a

wealth of cryptic maxims and proverbs about patterns on the board —

“Big

dragons never die,” for example, or “Nets are better than ladders.”

To put yourself in the mind of a player,

look at the empty board and imagine it’s your turn. Where would you go?

Kitani

began in the corner. Now imagine you’re the master, playing white. Do

you build

your keep at a safe distance, or set a collision course by making camp

nearby?

Once played, a stone resonates, exuding

influence so that it becomes hard to imagine the board without it. As

multiple

conflicts rage simultaneously in different areas, timing becomes

critical and

moves take on various flavors. This is what Kawabata means when he

writes,

“Black 69 was like the flash of a dagger … a diabolic stroke.” The

response,

White 70, is “a brilliant holding play.”

“But one may say too that the

64-year-old Master, gravely ill, played well to beat off violent

assaults from

the foremost representative of the new regulars,” writes Kawabata of

Shusai’s

eventual loss.

The master never recovered; his health

failed and he died a year later. Kawabata’s account jumps forward and

backward

in time between hushed moments in well-appointed rooms, where the two

men are

either waging war on the board or attempting to rest between battles.

At its core, “Meijin” is an exploration

of a larger moment when the traditions of the Edo Period gave way to

the

radical changes of the 20th century.

To

boldly go

Reading Kawabata, it’s hard not to

wonder what he, or Shusai, might have thought about the latest wave of

change

to rock the go world. On Nov. 23, Cho Chikun, a highly respected go

master, won

two games in a best-of-three match with DeepZenGo, an AI developed in

Japan. As

a young prodigy Cho had been the student of none other than Kitani and,

with

his victory, many in the go community breathed a sigh of relief.

In a surprise upset in March, Google

DeepMind’s AlphaGo AI won four of five games against Lee Sedol —

arguably the

best go player alive — and Cho’s victory went some way toward evening

the score.

“I felt as if I was playing with a

human, because DeepZenGo has both strong and weak points,” Cho said

after the

encounter.

Just as the innovations of Kitani and

his peers breathed fresh air into the game in the ’30s, advances in AI

are

introducing new possibilities today.

In its second game against Lee, the

AlphaGo AI stunned observers with a brilliant move that, by its own

estimation,

no human player would have chosen. Lee’s jaw actually dropped, he had

to leave

the room — and went on to lose the game. Revenge came in the form of

Lee’s Move

78 in the fourth game, now known as “God’s Touch,” which staggered

AlphaGo. The

machine made a series of erratic plays before resigning, handing Lee

his only

victory in the series.

The import of these advances is

thrilling, and professionals who have faced AIs say the experience

opened their

eyes to new kinds of play, raising the question: What could be next?

On the anniversary of the pivotal 1938

game that Kawabata immortalized, it’s exciting to ponder what the

future holds

for go — a game that has been at the center of so much human drama and

has now

become a forum for testing machine intelligence.

In March, a Chinese team working on

their own go AI announced plans to pit their machine against AlphaGo.

It seems the

possibilities really are endless.

To

view a move-by-move recreation of the 1938 game, visit bit.ly/2gc3igo and click through each play with the arrows.

Thank you for this most interesting and

informative article...Even before the Han Dynasty, board games were

viewed with

at best ambivalence. Confucius may or may not be referring to go, but

he

denounces the genre as a whole as a terrible waste of time...In

Kawabata's

novel, a go-playing foreigner appears, disapprovingly described, as I

remember,

for his poor etiquette. (Kawabata's fictional foreigners are

consistently

disagreeable.) I play go myself--but very badly, though I used to play

a

computer version, back when playing outrageously, violating all the

conventions,

would so throw off the program that i could win...It seems those days

are long

gone.