Spiders

Threads Roaming the Empyrean : The game of Weiqi

Andrew LO

and Tzi-Cheng WANG

By

chance I am free from official duties, and no guests are around ;

Discussing

military affairs on the table, we compete with a few stones.

Our

minds are like spider threads roaming the empyrean,

Our

bodies, like cicada shells joined to a withered branch.

There is

a single eye, like that of Prince of Xiangdong, and I truly am willing to suffer

defeat;

But the

world is split into two, and one can still hold onto a stalemate.

Who says

people like us still cherish time?

We have

no idea that the shen

star shines across the sky, and the moon has sunk.

Huang

Tingjian (1045-1105), “Second Poem on Weiqi for Ren Gongjian”

|

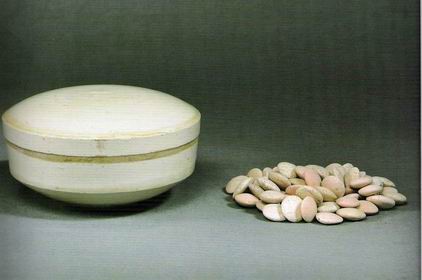

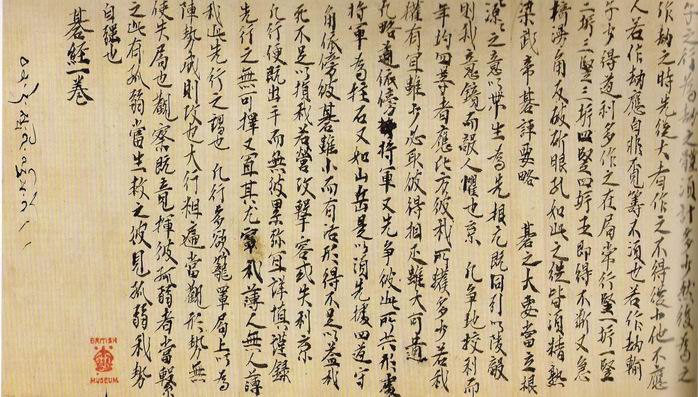

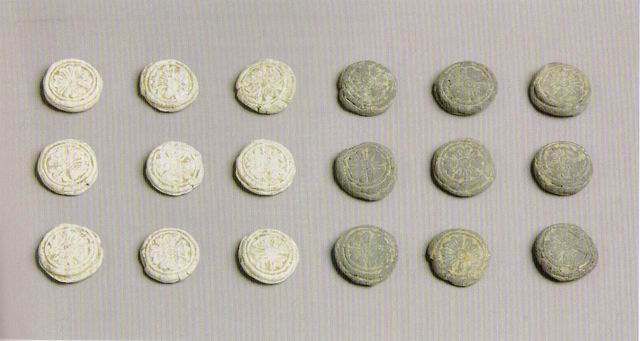

Weiqi

pieces and container.

China

; Song dynasty (906- 1368)

|

Glazed

porcelain container, ceramic pieces ; height of box : 10,5 cm

Weiqi

pieces are frequently found in Song-period tombs, testifying to the

growing popularity of the game. Both pieces and containers are often of

ceramic, while in the Ming (1368-164) and the Qing (1644-1911) periods,

stone pieces and wood containers were favored.

|

Weiqi and its Korean and Japanese

derivatives, baduk and go, comprise East Asia’s consummate board game of

skill. At least as old as chess, and arguably even more intellectually

challenging, weiqi seems deceptively simple at first glance. The game is played

by two players on a board marked with a grid (now standardized at nineteen

lines), each payer using a set of identical disk-shaped pieces. The players take

turns placing their pieces on the interstices of the grid in an attempt to

surround each other’s pieces, and the winner of the game is the player who

ends up with the most pieces that are not surrounded. Despite its apparent

simplicity -- the rules are few and

the pieces have no directional moves as in chess – the possible permutations

are almost infinite. It is significant that weiqi has become a favorite game of

mathematicians in the West. At present, no computer has been able to defeat the

top weiqi players, which suggests that the game requires a type of predictive

ability that is not purely mathematical.

Weiqi,

even more than chess in Western Asia and Europe, was crucial to the leisure of

the Chinese elite. It became a source of inspiration for the literary and visual

arts, but from the Tang period (618-907) onward, weiqi was considered an

indispensable cultural accomplishment alongside the arts of calligraphy,

painting, and the playing of the zither. As such, its role in Chinese culture

extended far beyond the sphere of games ; skill at weiqi, no less than the other

accomplishments, was a measure of a person’s claim to a place in the cultured

elite of pre-modern China.

The

beginnings of Weiqi and the material record

Huang

Tingjian’s famous line of “spider threads roaming the empyrean” captures

the essential quality of a player’s mind in joyful exploration of the

strategic possibilities of the game. This panegyric on the excellence of the

game for the mind is a far cry from the disparaging view of weiqi held by

Confucius, who once said grudgingly that playing games like bo and yi (another

term for weiqi) was better than being idle. Confucius could not have foreseen

that weiqi would become the board game played for the longest period in China,

having an unbroken history of more than two thousand years.

A

legend of the Warring States period (475-221 BCE) attributes the invention of

weiqi to the mythical Emperor Yao, while the poet Zhang Hua (230-300 CE) noted

that Emperor Yao invented weiqi to teach his unfilial son Danzhu, adding that it

also could have been Emperor Shun who invented the game to teach his slow son

Shangjun. Few people believe these theories, and the current view is that weiqi

probably can be dated to at least the year 548 BCE, when the indecisiveness of

installing a king on the throne was compared to a yi player raising a stone but

unable to decide where to play it. Most scholars take the term yi here to refer

to weiqi, and this is supported by a reference in Yang Xiong’s (53BCE – 18

CE) dictionary Fangyan (Dialects) : Weiqi is referred to as yi. Everywhere east

of the passes and in the region of Qi and Lu, it is referred to as yi. If we

cannot be absolutely sure that references to yi before the Han dynasty

(206BCE-220CE) refer to weiqi, we can find numerous literary references to the

game in the Han dynasty, leaving no doubt that weiqi was popular then.

Boards

and stones

|

Weiqi

board

From

a tomb in Wangdu, Heibei Province

China

; Eastern Han dynasty (25-220 CE)

Stone

; width 69 cm

|

Collection

of Heibei Province Cultural Relics Research Institute

This

is the earliest complete weiqi board in existence. It is marked with a

grid of 17x17 lines, the format that is known from literary texts to have

been standard at this time. During the tang period this was replaced by a

19x19 lines grid, currently used in China, Korea, and Japan. The 17x17

grid still survives in the Tibetan version of the game.

|

Although

the literary evidence suggests that weiqi already was played before the Han

dynasty, the absence of material evidence for the game at this early stage

raises questions as to how popular it was at the time. By the Han dynasty,

however, occasional finds of boards confirm weiqi’s growing popularity

(although these boards are still far less common than liubo sets at this time ;

see section 10), and also hint the game was still in a relatively early stage of

development. The earliest extant weiqi board is a fragment found at the

mausoleum of Emperor Jing (156-141 BCE) Although it is not possible to determine

how many lines comprised the grid, it has been suggested that the grid may have

been seventeen by seventeen lines. Certainly the seventeen-by-seventeen grid was

in use at this time, as shown by a stone board from a tomb of the Eastern Han

dynasty (25 - 220 CE) in Wangdu, Hebei Province (Fig 15:1) and another from the

tomb of the official Cao Teng (mid-second Century) in Boxian, Anhui Province. A

stone board with a fifteen-by-fifteen grid from a tomb in the middle or late

Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE) in Xianyang, Shaanxi Province, however,

shows that variants were also in existence at this time ; such variants may have

survived as late as the Tang or even Liao period (907 – 1125)

|

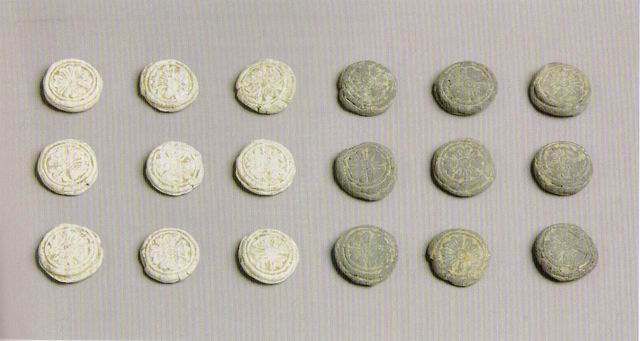

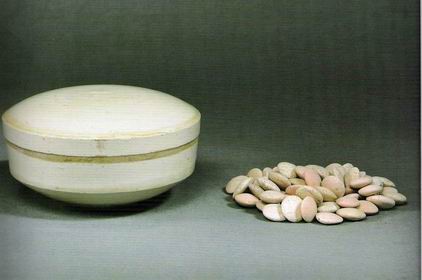

Weiqi

pieces

China;

Liao dynasty (907-1125)

Ceramic;

diameter 1.59cm each

Polumbaum

Collection

|

Most

later weiqi pieces are plain, but early pieces such as these are

occasionally decorated. Pieces similar to these have been found in Liao-period

tombs.

|

The

earliest nineteen-by-nineteen board found thus far is a porcelain example from

Anyang, Henan Province, dated to 595 in the Sui period (581-618). Another early

example is from the tomb of Ran Rencai (598-652), Prefect of Yongzhou during the

early Tang period. It is not possible at present to pinpoint the exact date when

the 19x19 board used today became the popular choice. The Yijing ( Classic of

Arts) by Handan Chun (fl. 192-220) mentions a 17x17

board, but the Qijing (Classic of Weiqi) of the Northern Zhou period

(557-81) discusses strategy based on a nineteen-by-nineteen board, as does the

manual Wangyou qingle ji (A Collection of Pure Joy to forget Worries) of the

Southern Song period (1127-1279). Thus it is possible that the

nineteen-by-nineteen board came into common use from the Tang period onward.

Since

the Song period (960-1279) or earlier, the gaming pieces have been standardized

as disk-shaped, but there also may have been squarish weiqi stones at an early

stage of the development of the development of the game. A late second-century

tomb in Bo District, Anhui, has yielded 122 green stones, each measuring I

centimeter square and 0.3 centimeter thick, which may be weiqi pieces ; 272

black and white stone pieces have been excavated from the tomb of Liu Bao in Zou

County, Shandong Province, dated to 301. The aforementioned Yijing states that

150 pieces were used by each player, but with the introduction of the

nineteen-by-nineteen board, this number probably increased to the 180 white and

181 black pieces currently employed. Weiqi pieces are relatively common in tombs

of the Song and Liao periods, reflecting the increased popularity of the game

(Figs; 15.2, 15.3). Various materials were used for the pieces, including

ceramic, varieties of stone such as agate and (more rarely) jade, shell, and

wood. Early containers for pieces were often made of porcelain or celadon, but

from the Ming period (1368-1644), lacquered (Fig. 15.4) or plain wood containers

(Figs. 15:5, 15 :6) were most prized. Woods used include hongmu and the

highly prized huang huali, which also was used for boards, the lines

inlaid with silver or brass (Fig 15:5).

|

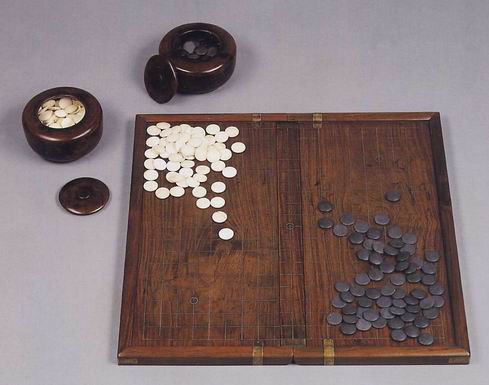

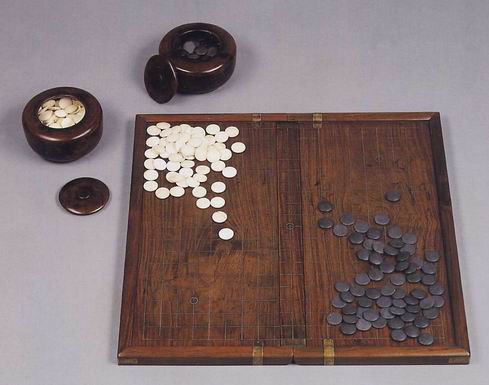

Weiqi

board, containers, and pieces

China

: late Ming dynasty (1644-1911), or early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), 17h-18th

century

Huanghuali,

inlaid with silver (board), Huanghuali

(containers), stone and bone (pieces); width of board 48.3cm,

height of containers : 7cm

Diameter

of pieces: 2.5cm

Nicholas

Grindlay

…

|

|

Paintings

No

other game in China – or indeed, anywhere else in the pre-modern world –

provided such continuous inspirations to artists as weiqi. Paintings depicting

weiqi survive from as early as the Tang period through the end of the Qing

(1644-1911) and are still produced in contemporary times. This is not

surprising, since (as discussed below) weiqi became an essential cultural

accomplishment in China and consequently a component of the scholar’s

self-image, just as much as composing poetry or writing calligraphy.

|

The earliest extant depiction of weiqi

is a painting from the seventh-century tomb of an official in Astana, Turfan,

which depicts the wife of a sixth-rank official placing a weiqi stone on the

board with her index and middle fingers in an attitude of full concentration

(Fig 15:7). Although her opponent is not shown, it was likely a woman, as board

games played with members of the opposite sex are virtually unknown in Chinese

art. |

Another example of this genre is a painting attributed to Zhou Wenju

(mid-tenth century) entitled Heting yidiao shinü tu (Ladies playing weiqi and

Fishing at a Pavilion Overlooking a Lotus Pond) ; a fifteenth-century porcelain

bowl decorated with the four cultural accomplishments also show women playing

the game.

|

These examples notwithstanding,

depictions of women playing weiqi are rare before the Qing dynasty.

Instead, weiqi characteristically appears in paintings of emperors or,

more frequently, scholars (see fig 1:2)

Scholars

Playing Weiqi under Pine Trees

China;

Yuan

dynasty (1279–1368)

Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk; 122.24 x 69.06 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Gift of funds from Ruth and Bruce Dayton

|

|

At least two other

paintings of weiqi attributed

to Zhou Wenju survive, both depicting emperors engaged in the game. The

first entitled Minghuang hui qi tujuan (The illustrious Emperor [Xuanzong]

at a weiqi gathering), and the second, Chong ping hui qi tu (A weiqi

gathering in front of a double screen). The latter, which exists in a

number of later versions (Fig 15:8) depicts King Li Jing (943-961) of the

southern Tang kingdom and his three brothers, with the

king in the center watching two of his brothers play on a

nineteen-by-nineteen board.

|

Weiqi is depicted simply as a pastime

in these two paintings, but in other depictions it may have had a more symbolic

role. A mural painting from the tomb of Zhang Wenzao, dated to 1093, shows two

people playing weiqi, with one onlooker at center and three attendants to

the right. The scholar Luo Shiping interprets the two players as one Daoist and

one Buddhist monk, and the onlooker as a Confucian, suggesting that the looker

in the center symbolizes the central role of Confucianism in the unification of

the three teachings.

Whether this interpretation is

correct, other depictions of weiqi from the Song period onward imply that

weiqi was viewed as an activity particularly appropriate for scholars.

For instance, in Liu Songnian's (fl. 1174-1210) Jiu lao tu (The Nine

Elders)-the title of which refers to the retired poet-official Bai

Juyi and eight friends who met in Luoyang in 845 -two old gentlemen are holding

bowls containing weiqi stones and happily playing the game, as another

friend looks on at center. In an

anonymous set of four paintings depicting the Shiba xueshi tu (The Eighteen

Academicians), a celebrated group of outstanding scholar-officials of the

early Tang period, the second painting shows two of the academicians playing weiqi,

with

two others looking on. Two elders play weiqi in the center of another

anonymous painting, Luoyang qiying hui (Meeting of the Virtuous Elders at

Luoyang), which depicts one of the famous eleventh-century meetings of

thirteen friends including the retired Grand Tutor Wenyan Bo and the academician

Sima Guang in the house of Fu Bi, Duke of Han.

In paintings such as these and the many examples from the Yuan

(1279-1368) and Ming periods, weiqi has become a visual marker of

refinement and the cultivated mind no less potent than the scholar's other

visual props i.e., scrolls, antiques, and the zither.

TREATISES

AND MANUALS

The use of weiqi as a metaphor for philosophical and political

discourse is found in the earliest surviving treatise on the subject, Ban Gu's

(32-92 CE)Yi zhi (The Meaning of

Yi). Here Ban compares the games of bo (liubo) and weiqi, and

notes that bo is less fair because of its element of chance through the

use of dice. Ban states that weiqi is symbolic of heaven and earth, and

that it mirrors the government of emperors and kings, the expedient measures

of the five hegemons of the Spring and Autumn period (770-475 BCE), and military

matters of the Warring States period. He then writes,

In the enjoyment [of the game], one may exert oneself and forget about food,

so full of joy that one forgets one's worries, and if we raise this state to a

higher level, it is like Confucius' summation of himself.

There is joy without wantonness, and sorrow without self injury, and for a comparison in the Book of Poetry, it is like the

poem "The Singing Fishhawks." If one disentangles silk from a spindle,

one can understand the soft nature of silk. Yin and yang come in

cycles, and applying this principle to cultivate one's nature, it is like the

energy of Peng Zu. Outwardly, it seems to be non-action, quiet, and

understanding purity and not seeking fame or profit, holding on to the meaning

of the Way. ... Living in seclusion and giving free rein to his words, keeping

away from fault and lying low, it is like Yuzhong. This is truly delightful.

In this passage, by drawing

comparisons with lines from the Confucian Analects and with Daoist

philosophy, Ban attributes a philosophical depth to the game that is taken up by

later writers. For example, the title of the aforementioned Song-period manual Wangyou

qingle ji (A Collection of Pure Joy to Forget Worries) also refers to this

line from the Analects, and Ban's concluding line of living in seclusion

becomes "sitting in seclusion" for Wang Tanzhi (330-75), a phrase that

becomes a key metaphor for the game. Two other important early treatises include

Yi shi (The Battle Arrays of Yi) by the poet Ying Yang (d. 217),

and Qi pin xu (Preface to A Grading of Weiqi [Players]) by Shen

Yue (441-513).

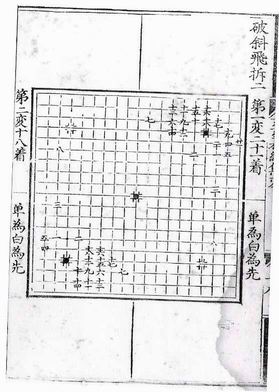

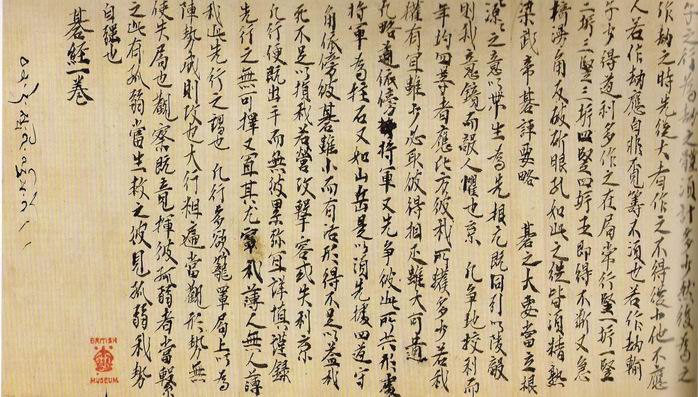

Qi Jing discovered in Dunhuang cave |

Manuals on weiqi were

compiled as early as the Han dynasty, but the earliest extant manual on weiqi

strategy is the aforementioned Qi Jing from the Northern Zhou period

(Fig. 15:9). The manuscript lay dormant for centuries in a library in the

sealed caves of Dunhuang, Gansu Province, until the discovery of the collection

at the end of the nineteenth century. The manual is now in the British Library,

and although its existence had been noted by scholars, its importance for our

understanding of the game was revealed only recently by the modern scholar Cheng

Enyuan. Cheng has shown that many concepts in the subsequent extended text on weiqi

strategy, the Qi jing shi san pian ( Classic of Weiqi in

Thirteen Chapters, ca. 1049-1053), already had made an appearance more than

four centuries earlier. Cheng notes the major contributions of the Qijing, including

strategies and tactics not found in the Qi jing shi san pian, certain

aspects of how points were counted in the game, the inclusion of a summary of

Emperor Wu's (r. 502-49) lost work Qiping (A Critique of Weiqi), and a

chapter on ladder formation problems.

The Qi jing shi san pian, probably

compiled by the academician Zhang Ni, is modeled on the thirteen chapters of Sunzi

bingfa (Sunzi's Art of War) of the late fifth century BCE. The link to

military strategy has been a consistent thread in the history of weiqi in

China. The Qi jing shi san pian was included in the most famous manual of

the Song period, the aforementioned Wangyou qingle ji compiled by Li

Yimin, a weiqi player in attendance at court in the early twelfth

century. Interestingly, this manual

also purports to record earlier games of weiqi, such as those between the

warlord Sun Ce (175-200) and Lu Fan (d. 228), those of Emperor Xuanzong

(r712-56) of the Tang against Zheng Guanyin, and those between masters of the

Northern Song period (960_1127) held in various temples and scenic spots in the

capital, Kaifeng. There is also a game entitled “Diagram of the four Immortals

at Chengdu Prefecture,” dated to 1094, which is the earliest record of team

play (by Liu Zhongfu and three other players). Although not all these games –

especially those attributed to the early players – may be genuine, they show

an interest in famous weiqi contests that has continued in China (and in Japan)

down to the present. It must be noted that the historiography of weiqi

anticipates that of chess by several centuries.

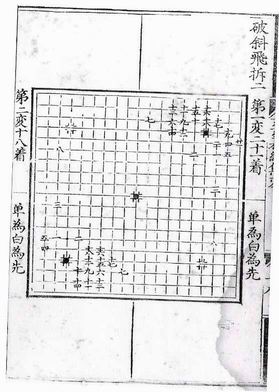

| From the Yuan period, only the

Xuan xuan qi jing (The Mystery upon Mystery Classic of Weiqi) has survived (Fig

15:10), but in later periods manuals proliferated.

|

|

At first count, there are

seventeen extant manuals from the Ming period, and fifty-five from the Qing. A

few are introduced briefly here to give a flavor of these works.

1 Shi qing lu

: a record of pleasing one’s emotion, compiled by Lin Yinglong 1524.

Interestingly, 384 diagrams in this work originated in the manual Juesheng tu

(Diagrams of Competition), compiled by the Japanese monk Kyocho (Xuzhong), who

lived in Hangzhou during the Hongzhi era (1488-1505). Lin notes that the phrase

“pleasing one’s emotions” comes from the story of the prime minister Wang

Anshi (1021-86), who was a horrible player ; whenever he lost a point, Wang

would give up and say, “I wanted to please my emotions. Why should I trouble

my mind to such an extent?” Although the title would attract players of an

amateur literary bent, the first eighteen juan chapters are classified under

twenty military categories such as “proper troops”, “surprise troops”,

“guerilla warfare”, and others, which run contrary to the leanings of many

scholars.

2 Shi shi xian ji (Immortal

Secrets of Stone Chamber [mountain]), compiled by Xu Gu, who placed first in the

metropolitan examination of 1535. The edition is printed in red and black ink,

and the title refers to Ren Fang’s (460-508) story of the woodcutter Wang Zhi

of the Jin period (265-420), who went to Stone Chamber Mountain and encountered

several boys playing weiqi. After a while, one of the boys said that Wang should

leave, and getting up, he realized that the handle of his axe has rotted. Wang

went back his hometown, and none of his contemporaries were still alive. The

title of the manual refers to the secrets of the immortal boys, and the story

also reminds us of the long time it takes for immortal to finish a game, when

measured against human time.

3 Hui yi tong xuan pu (A weiqi

Collection to reach the marvelous realm), compiled by Zhu Changqian, with

preface dated 1609. Zhu Changqian

headed the princedom of Yi in Jiangxi province. The marvelous realm is a

standard of play for which all players aim, but which only master players can

attain

4 Yi sou (A garden of Weiqi),

compiled by Su Zhishi, circa the Tianqi era (1621- 27), with congratulatory

prefaces and poems by famous literati such as Chen Jiru. An edition printed in

three colors is extant.

5 Lufan jizuan wanhui xianji qi

pu (Lu princedom weiqi manual of a compendium of immortal secrets), compiled by

Zhu Changfang, 1634. Zhu Changfang headed the princedom of Lu in Henan Province.

6 Bu gu bian (Not an old

compilation), compiled by Wu Ruizheng, 1682. This is a rare example in

pre-modern china of something new being favored over something from the past.

7. Taohua quan yipu (The plum

blossom spring manual of Weiqi), compiled by the professional player Fan Xiping,

with preface dated 1765. The manual is named after the Plum Blossom Spring well

at the head-quarters of Gao Heng, Salt Censor of the Lianghuai area, who

sponsored Fan and printed the manual. This is a good example of the symbiotic

relationship between patrons and professional players that existed in the

eighteenth century.

Reflecting on the level of play

seen in manuals of the Song and Ming periods, the modern scholar Liu Shangcheng

notes that, while each manual may have had its marvelous and unique moves, the

skill level is relatively weak in overall play. From a modern viewpoint, some of

these moves do not make sense and the authors’ understanding of some of the

principles of the Qi jing shi san pian is inadequate.

These sentiments echo those of

the Qing national master Fan Xiping, who in 1765 compared the level of play of

the Ming period unfavorably with that of his time :

The players of the Ming period

had a general strategy for the game, but they did not bring out everything. They

only talked about attacking and defensive moves, fake and real moves, and about

the right or wrong flow of moves. At the beginning of the Qing period, the

players at the Garden of Weiqi Pleasure thought deeply with single purpose, and

went straight to the minute. In attacking and defensive moves, they created

finer attacking and defensive moves; for the fake and real moves, they created

finer fake and real moves; and in the right or wrong flow of moves, they created

finer right and wrong flows. They exhausted their own heroic abilities, and

became masters at their own right. Grand and upright, strange and unorthodox,

they surpassed the former players, and it was grand. The national players during

these thirty years are different. They compete for big or small gains in minute

areas, and decide on survival or defeat in the unfathomable. They exchange and

transform, and often preserve a sliver of ingenuity. They play a stone three or

four spaces away and everywhere they think of the whole game.

PLAYERS

Although

it is likely that commoners also played weiqi, it was the elite who adopted it

as a game of high culture. The famous weiqi players and games of antiquity

already listed in compendia by the Ming period, a historiographical tradition

that has continued down to the present and parallels that of chess. In this

section, we explore the main categories of players and consider the role of

weiqi in the elite society.

Emperor and the Upper

Class

Not all

Chinese rulers enjoyed weiqi, but there are examples of emperors from almost all

of the major dynasties who did. These include Emperors Jing, Wu (two of whose

works on the game are extant), Taizong (r 627-49) , Taizong (r. 976-97), Huizong

(r1101-25), Wenzong (r1328-32), Taizu (r. 1368_98), and Chengzu (r 1402-24),

among others. At least three rankings of players were held by imperial order in

the early history of the game, in the Yongming era (483-93), the Tianjian era

(502-19) and the Datong era (535-45). Ranking probably followed the nine grades

in Handan Chun’s aforementioned Yijing:

- 1)

entering into divinity;

- 2)

sitting in illuminations;

- 3)

possessing form;

- 4)

reaching the sublime;

- 5)

using intelligence;

- 6)

minor ingenuity;

- 7)

competing with strength;

- 8)

appearing foolish;

- 9)

holding on the crude.

There are different interpretations of these grades. Some

regard the ranking in a descending order of skill, while He Yunbo argues that

the last two ranks may be interpreted as encompassing two levels each: an

initial level for beginners, and a higher level when the player has come full

circle and only seems to be foolish or crude.

Handan’s inclusion of weiqi as one

of the arts was followed by Liu Yiqing (403-444) in his Shishuo xinyu (A new

account of tales of the World), which listed weiqi in the “skillful arts”

section, along with calligraphy and painting. The Six Dynasties period

(265-589), in fact, is noted for the heightened aesthetic sensibility of the

upper class, and it is clear that the game became associated with elegance at

this time. As we have noted, the scholar-official Wang Tanzhi regarded weiqi as

“sitting in seclusion,” and the monk and poet Zhi Dun (314-66) regarded it

as “conversation with the hand”. “Sitting in seclusion” denotes

aloofness from the mundane world, and “conversation with the hand” may be

seen as an extension of upper class philosophical debates of the period. The

Qijing describes weiqi as “an elegant pastime amongst games”, and the

scholar Yan Zhitui (ca 520 – ca 590) noted that it was quite an elegant game,

though distracting, and one should not make a habit of it. By the early eight

century, weiqi had joined calligraphy, painting, and the playing of the zither

to form the four accomplishment to which every gentlemen and lady ought to

aspire, and the poet-official Liu Yuxi (772-842) even noted that people of his

time would not be ashamed of bas calligraphy, but would blush if accused of

being bad at weiqi.

Professional

player

Professional

players seem to have first appeared during the Tang period as court attendants.

In the Song, professionals could be categorized further into court attendants,

weiqi masters under the patronage of officials, an players who eked out a living

in shops and taverns. By the Ming period, professional players were able to make

a living without imperial patronage, and Wang Shizhen (1526-1590) noted players

from the Yongjia school (in present-day Zhejiang Province), the Xin’an school

(in present-day Anhui Province), and the capital. Qian Qianyi (1562-1664), an

avid watcher of weiqi, composed the following description of two masters of his

lifetime, Fang Weijin and Wang Youqing :

Weijin is deep, quiet, and at ease. He

observes with his spirit in an aloof manner. When he plays, the other player

will be deep in thought, with eyes wide and intense, hands trembling and cheeks

red, while Weijin will close his eyes and sit upright, as if in Budhist

meditation. After a long time, when the other player has just played his piece,

Weijin will respond casually. The two stones will ring out, and he will just

blink once.

Youqing

is deep, brave, refined, and tough. He is unique and outstanding. Each time he

meets an opponent, the light from his eyes will explode and penetrate the suares

of the board. He will play an extraordinary move and beat the opponent. In

horizontal, vertical, turning, and exploratory moves, he is like a beautiful

stallion chasing the wind, or a hungry eagle spilling blood. Pushing the board

away in a win, he throws his hat and cries out aloud, and even the opponent who

has suffered capture and had his pieces thrown aside will clap his hands and

say, “Wondeful!”

When

Weijin plays a stone, it is like a nail fixed to the board. He will not waver

the least bit, and he will not have made a mistake. If someone makes a fuss,

then after the game is over and the stones are recounted, no matter if it is

one, two, or whatever number of stones in error, he will not mind, as if he had

not played the game.

Youqing

keeps winning and looks down on his opponent, and occasionally he will make a

mistake. After the mistake, he will fold his hands and think well. In a while,

he will play an extraordinary move, and it is like crossing a torrential river,

or cutting his way through a fortified pass. In this case he cannot retract his

first move, but the opponent also has no way of withstanding Youqing’s

extraordinary move, and Youqing will have save himself from his mistake and win.

People say that in Youqing’s game, an opponent does not fear when he plays

correctly, but does so when he makes mistake. If he makes a small mistake, he

will have a minor win. If it is a big mistake, he will have a major victory.

In

a later generation, the scholar Yan Ruoju (1636-1704) listed fourteen sages of

his period, and it is notable that the weiqi masters Huang Longshi was among the

group, which included the giants of scholarship Huang Zongxi and Gu Yenwu. The

level of play in premodern China reached its height in the eighteenth century,

and the two acclaimed masters of the time were Fan Xiping and Shi Dingan, both

from Haining, Zhejiang. The two have been described as follows :

Xiping is wonderful and lofty,

like a divine dragon shifting its shape, its head and tail unfathomable. Dingan

is profound, meticulous, precise, and strict, like an old steed galloping

without a misstep. Commentators liken them to the poets Li Bo (701-762) and Du

Fu (712-770), which is most fitting

The two did meet and played at Danghu,

Zhejiang, in 1739. Both also compiled manuals, Fan the aforementioned Taohua

quan yipu, and Shi the Yi li zhi gui (Essentials of the principles of Weiqi

1763).

Despite

the sporadic sponsorship of the court, officials, and salt merchants in

pre-modern China, the professional system could not nurture and sustain healthy

competition or new generation of players. The level of play declined after the

mid-nineteenth century, and Chinese players were shocked by the skill of the

Japanese players who landed on their shores in the early twentieth century. It

is only from the 1980s onward that a sound system of competitions was

established, and China began to catch up.

Shidaifu players

The term

shidaifu qi (weiqi of the scholar-officials) was used by He Wei (ca. 1086-1150)

to describe the playing style of the scholar Zhu Buyi, who was in the capital

for the civil service examination in the Shaosheng era (1094-1098). A friend

dragged Zhu to a temple courtyard to watch the masters, which included the

national master Liu Zhongfu. The crowd then urged Zhu and Liu to play. Zhu asked

Liu for a handicap, which Liu cautiously refused, only letting him play first.

Zhu lost the game by three stones, and asked for a handicap again. Liu replied

that Zhu had played very well in the beginning, but it seemed that he had not

given his best, and so refused again. The two then agreed to take turns playing

first ; after thirty or so stones were played, Liu asked for Zhu’s name, and

the onlooker answered with a pseudonym. Liu then mentioned the great player Zhu

Buyi, and the crowd then told him the truth. Liu met Zhu several times after

this but did not talk of weiqi, as he did not want to feel the shame of a

national player losing.

He Wei

came from a scholar-official background, and betrays a bias toward his own class

in this story, but it is clear that by the Song period, a distinction had been

made between the professionals and the amateur scholar-officials. Unable to

compete with the professional’s total dedication to the game provided, the

literati developed the game in new directions (in terms of play but not in

competition), or enjoyed watching others play and writing about their

observations. The literati giant Su Shi (1037-1101), who did much to shape

literati culture and who admitted to not understanding the game, left us with

this famous line from his poem entitled “Watching Weiqi, with Preface” :

“Winning, one is happy for sure, but there is also joy in losing”

Over the

centuries, numerous literary works have been written on weiqi, helping to lift

the game to the level of art and elegance. Rhymed prose compositions on various

types of board games were popular from the Han to Tang periods, and those on

weiqi by the scholar-officials Ma Rong (79-166), Cai Hong (late third century),

and Cao Lu (D. 308), and by emperor Wu of the Liang (mentioned above) and

Emperor Xuan (r. 555-62) of the Later Liang, are notable.

Poems on

weiqi increased significantly in number from the Tang period onward, and as

there is immense pleasure in watching a game, this became a major theme. The

aforementioned literary giant Qian Qianyi wrote at least thirty poems on

watching weiqi, including the following.

Six

Quatrains on Watching Weiqi : Number Four

The

old man {Fang} Weijin can discuss military strategy,

halfway

through a game he can let a young player escape.

When

a game draws to an end do not be fixated on capture;

in

the shade of the flowers, the sunlight seeps through and goes round the board.

Six

Quatrains on Watching Weiqi at Jingkou: Number One

Watching

a national player at the end of a match,

it

is late autumn in the three mountains, and his sideburns have turned white

A

clear lamp shines on him, it is all like a dream;

The

board has been empty for a long time, and there is no date for a further match.

Six

Quatrains on Watching Weiqi at Wuling: Number Three

Black

and white so clear when one plays the stones;

it

is now clear which is the male and female rabbit in the game.

One

cannot be sure who the national masters are in the world;

so

watch weiqi the whole day, but do not play.

While

weiqi generally was not associated with gambling (as were playing cards and tile

games), references to wagers made by players on the outcome of games are not

infrequent. True to the refined nature of the game, money rarely is mentioned,

and it may be that the object of the wagers was mainly to increase the

excitement of play. In the case of a game played by General Xie An and his

nephew Xie Xuan during the battle of Feishui in 383, a villa was at stake. Often

among scholar-officials, the wager was not so much a gain for winning as a

literary penalty imposed for losing. For example, Xu Xuan (916-91), who played

with Liu Huan and lost, had to write a poem. Similarly, the retired Prime

Minister Wang Anshi(mentioned above) wagered with Xue Ang and lost, and had to

write a poem for him. Elegant commodities also were wagered, as in the case of

the painter Wen Tong (1018-79), who won tea and ink from his friend Ziming

twice, and won an ink stick made by the master ink maker Zhang Yu of the Five

Dynasties period (907-60). Naturally, Kong wrote a poem to remind Ziming.

Women players

In

the year 3 BCE, the official Du Ye argued that, just as the games of bo and

weiqi were exclusively male pastimes, so too were the affairs of state, and the

Dowager Empress should stop interfering in these matters. It is clear from

Han-period literary references to women playing liubo, however, that this game

at least, was not an exclusively male preserve. From the Tang period onward,

there is ample literary evidence for women playing weiqi, although only thirty

five specific names of female players over the centuries listed in Huang Jun’s

Yi ren zhuan (Biographies of Weiqi players). There were also very few

professional women players but it is interesting to note that a few immortals

who supposedly taught the masters were women. The official Xue Yongruo (early

ninth century) recorded the following story of Wang Jixin, the most famous weiqi

player in attendance at the court of Emperor Xuanzong. During the emperor’s

flight to Sichuan in 756 due to the An Lushan Rebellion, Wang found refuge in a

place in the mountains with an old woman and her daughter-in-law. At night he

heard the two women, in different rooms, exchanging weiqi moves verbally in the

dark, and in the end, the old woman won by nine stones. Wang noted down all

thirty-six moves, and the next day, the daughter-in-law taught him a few. When

he begged for more, and tried his utmost to understand the win of nine stones,

but failed. He named the layout “Deng Ai opening up the area of Shu”

according to Xue, the diagram remained, but was not understood.

In

he Northern Song period, there is the legend of the master player Liu Zhongfu

playing with the old lady from Mount Li which may have been influenced by the

Wang Jixin story. There are also numerous scenes depicting women players in

Chinese drama and novels. An interesting example is the scene from the drama

Yuzan ji (The Jade Hairpin), written by Gao Lian in 1570, in which the official

Zhang Xiaoxiang (1132-70) tries verbally to seduce the Daoist nun Chen Miaochang

over a game of weiqi.

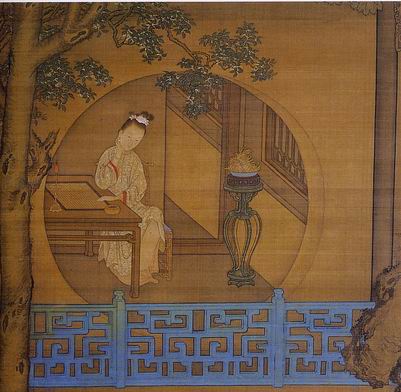

Broken tryst - Qing 19th Century |

While

paintings depicting women playing the game are rare from the Song through the Ming period, in the Qing they become more common. In such paintings (Fig 15:11),

however, weiqi often seems to evoke romantic connotations rather than the

philosophical and scholarly associations found in literati painting.

|

Given

the hold that weiqi exerted on the Chinese elite for two millennia, it is nor

surprising that the game spread to the surrounding regions over which China

exerted its greatest cultural influence – namely, Korea and Japan. Although

the date of its adoption in Korea is not certain, weiqi seems to have been

played there at least as early as the seventh century, by which time it had also

been transmitted to Japan. It was played on a limited scale in Nepal, Sikkim,

and Tibet but did not spread westward, most probably because, although no less

intellectually demanding than chess, its pieces lacked the figural imagery that

makes chess so compelling. If its appeal outside East Asia remained restricted

by its cerebral, even abstracted nature, within its homeland weiqi inspired a

rich cultural legacy. When we read about holding the dislodged tooth of a dragon

in our hands, which guarantees invincible strategies in play, or of the monk

Kumarajiva (343-413), who, after picking up the captured pieces of his opponent

at the end of the game, left the shapes of a dragon and phoenix in the empty

spaces of the board, we have entered a world of marvelous mysteries.

Extrait du catalogue de l'exposition de Octobre 2004 :

Asian Games ,

The art of contest.

Retour

Go

Dernière

modification le

29/11/2012